The Brewster Buffalo was an unlikely fighter plane, designed to be easy to build and operate. It was also a terrible success.

The Brewster Buffalo was an Unlikely Fighter Plane—But Finland Loved It is a blog post about the Brewster Buffalo fighter plane.

During World War II, the Finnish version of the Brewster Buffalo, which was manufactured in the United States, proved to be a formidable opponent for elite Soviet, German, and British fighters.

It was an odd juxtaposition. A few stubby, blunt-nosed US-built aircraft with swastika insignia climbed eastward on a June day in 1942 to intercept British-built fighters with red Russian stars.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the globe, in Midway Atoll, the same American-made fighters were involved in a disastrous encounter with the Imperial Japanese Navy.

The Brewster Buffalo was a barrel-shaped American fighter. The Finns and the US Marine Corps both flew the aircraft, although with quite different results.

The Marine squadron VMF-221 lost 13 of its 20 Buffaloes near Midway, while the Finns routinely outshot their Soviet opponents by orders of magnitude.

To illustrate the distinction, you’ll need a strategic and tactical background.

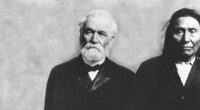

The Mannerheim Cross, which was awarded in 2nd and 1st grades, was named after Finland’s commander in chief during World War II, Gustaf Mannerheim, and was given for outstanding courage or important service.

Brewster pilot and ace Ilmari Juutilainen was a two-time winner of the award. © Military Museum of Finland, CC BY-SA 4.0

Finland’s geography, which shares borders with Sweden and Russia, has influenced the country’s propensity for war. Since 1814, when Norway gained independence, Sweden has remained neutral.

However, Finland and its forefathers had fought Russia a dozen times, mainly throughout the tsarist period and into the early nineteenth century. Many Finnish troops sat back to drink vodka during the worst of the weather.

The world was shocked when the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed a non-aggression agreement in August 1939.

Three months later, Russia invaded Finland, claiming the Karelian Isthmus north of Leningrad (modern-day St. Petersburg).

The ensuing war was known as the Winter War, and it continued until the spring of 1940, when Helsinki succumbed to Moscow’s demands, losing 11% of Finnish territory.

The Ilmavoimat, the Finnish air force of the time, was a little force. Its combat strength ranged from 110 to 166 aircraft, excluding training and liaison aircraft.

The collection included kinds from the United Kingdom, France, Holland, and Italy, among others. The objective of standardization was clear, but it was difficult to accomplish.

Meanwhile, in September 1939, World War II broke out as panzer forces stormed throughout Europe. The Germans invaded Norway in April 1940. Due to Finland’s formal neutrality, Wehrmacht troops were permitted to pass through its territory on their way to Norway.

Helsinki and Berlin became de facto allies when Germany attacked Russia in June 1941, despite Finland’s refusal to join the Axis. The US stopped all assistance to Finland at that time, including replacement aircraft and components.

The Finns were among the best fighter pilots in the world, man for man. The Ilmavoimat, despite its size, aimed to develop world-class aviators to combat the nation’s most probable adversary—Russia.

In order to do this, the Finns sent top pilots to other countries in the 1930s to collect knowledge about fighter aircraft.

Capt. Gustaf Erik “Eka” Magnusson was known as the “Father of Finnish Fighter Tactics” at the time. During the 1930s, he sought out exchange trips in France and Germany, where he evaluated a variety of European fighters, eventually leading to Finland’s acceptance of the Fokker D.XXI fixed landing gear monoplane from Holland.

Magnusson incorporated lessons gained from France and Germany and applied them to Finland’s fledgling fighter arm with the help of Lt. Col. Richard Lorentz. As a consequence, they were able to achieve remarkable combat success.

Magnusson led the most effective fighter squadron in his air force as the commander of Lentolaivue (LeLv) 24. LeLv 24 claimed 781 aerial victories against 33 losses during the 1941–44 Continuation War while flying Brewsters and Messerschmitt Me 109s, a ratio of almost 24-to-1.

The Finns realized the value of more flexible formations and were ahead of the Luftwaffe in adopting the subsequent world-standard four-plane flight.

The ideal fighter flight consisted of two four-plane divisions, each with two parts of leader and wingman, and was occasionally altitude-staggered.

The Finns joined the US Navy in training wide-angle firing out to 90 degrees, rather than the 30- to 45-degree “pursuit curve” flown by almost every air force. For the unavoidably outmanned Finns, the ability to strike at full deflection became a force multiplier.

Regardless of the usual exaggeration associated with a unit’s score, the wildly uneven results screamed loudly. Magnusson took the initiative and led from the front.

He had 5.5 personal kills when he left LeLv 24 in 1943 to command a flight unit, commanding a roster that comprised Finland’s best fighter pilots.

The Finnish government examined three American aircraft, each an all-metal monoplane with retractable landing gear and an enclosed cockpit, to modernize its fighter arm in the run-up to the conflict, including the Grumman F4F and the Seversky EP-1, an export version of the P-35.

Helsinki concentrated on Brewster’s new naval fighter, the F2A-1, since the Grumman types were not yet ready and the EP-1s had gone to Sweden.

Because Finland was not at war, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s government deemed the F2As “surplus,” and Helsinki got 44 before the embargo took effect.

Brewster Aeronautical Corp. was a descendent of Long Island, New York-based Brewster & Co., which began as a carriage manufacturer in 1810 and subsequently expanded to produce luxury vehicle bodywork and aircraft components.

Brewster Aeronautical had modest success with the SBN scout bomber for the US Navy and SB2A/A-34 dive bomber for various services in the mid-1930s and early 1940s, but none saw action.

With the Douglas TBD Devastator and Vought SB2U Vindicator dive bombers on carrier decks in 1937, the Navy had already entered the monoplane era. Brewster’s F2A-1 (tentatively the Twister, subsequently the Buffalo) and Grumman’s F4F-3 were the first monoplane fighters to arrive (tentatively Comet, later Wildcat).

In 1939, the Brewster, a significant upgrade over Grumman’s F2F and F3F biplane fighters, entered naval service. The F2A had hydraulically powered landing gear, which was much superior to the hand-cranked wheels used by its Grumman rivals.

The F2A also had a wide “greenhouse” canopy in the cockpit, giving pilots greater vision than most of its contemporaries.

The Wright R-1820 Cyclone nine-cylinder radial engine powered the prototype XF2A-1, which first flew in December 1937. The carrier USS Saratoga received less than a dozen of a typical early order of 54 production F2A-1s.

During the 1939 Winter War, the Roosevelt administration sent 44 Brewsters to the Ilmavoimat, despite the fact that the first six arrived too late for action.

Despite the fact that small Finland humiliated the Soviet Union in its territorial grab, inflicting almost four times as many fatalities on the Russians, the numbers won out.

After three months of war, the countries signed a peace treaty in March 1940. That summer, Brewster made up for its production shortfall by delivering the majority of the upgraded F2A-2s to the US Navy.

Buffalo was also delivered to the United Kingdom (Royal Navy and Royal Air Force), Australia (Royal Australian Air Force), and the Netherlands.

The RAF and RAAF fought Japan in Singapore, Burma, and Malaya in 1941–42, while the Dutch East Indies air force defended Borneo and Java until the Japanese overtook them.

The Finnish Brewsters, designated Model 239s, were remarkably identical to the Navy’s F2A-1 with Wright Cyclones.

Despite the type’s terrible combat history in the United States, pilots from a variety of countries liked flying it since it was quite fast for the time (300 mph) and had sensitive controls. It was given the name Taivaan Helmi (literally “Sky Pearl”) by Finns.

In 1940, researchers from the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough Airfield examined a Brewster and judged it to be much superior than the Buffalo’s later reputation.

The elevator control isn’t as responsive as the Spitfire’s or as sloppy as the Hurricane’s, according to assessors. “Once in the air, it accelerates quickly and has a strong initial rate of climb.” With a “excellent” forward vision, the approach to landing was flown at 90 to 95 mph. “

The aircraft settles down after a little float with no bounce, bucket, or swing,” most pilots said, “but the aeroplane settles down after a small float with no bounce, bucket, or swing.”

The metal ailerons of the Brewster impressed the assessors the most. They stated, “They are sharp and strong, and the stick forces are neither too light at low speeds nor too hefty at higher speeds.”

The pilots thought they were a big improvement over the fabric-covered ailerons of the Hurricane and Spitfire.”

The Brewster contract with Finland was completed in December 1939 at an average price of $54,000 per aircraft with 950 hp Wright R-1820 radials, without military equipment (guns, sights, etc.).

The first of the remaining 41 239s was delivered to Sweden in March, the month the Winter War concluded, after passing acceptance testing on three of them in the United States. It was equipped with three Finn-built Colt MG 53-2.50-caliber machine guns and one MG-40.30-caliber light machine gun at first, but was subsequently upgraded to four.50s.

A reflective gunsight and reinforced chairs were among the extras. Many fighters used telescopic sights with restricted fields of vision, or metal ring and bead sights, similar to those used in World War I.

The Finns developed a German-style reflector sight after realizing the benefits of wide-angle gunnery.

According to Finnish historian Kari Stenman, “a significant reason for excellent shooting results…was that every pilot was trained [by 1939] to hold their fire until within 50 meters of the target.” “Following the Winter War, a greater focus was placed on shooting abilities, with predictable consequences.

“Each fighter pilot school featured two gunnery camps, one for fixed targets and the other for flying targets. Then, for a number of flights, all rookies in the squadron were assigned as a wingman to a veteran until the veteran ‘released’ the pilot for regular duties.”

The Finnish Brewsters had to work in a harsh environment. North of the Arctic Circle, about a fourth of Finland is located. Helsinki, Finland’s capital, averages a high of 48 degrees Fahrenheit and a low of 37 degrees Fahrenheit.

Five months of the year average temperatures below freezing, with three of those months (December through February) having highs in that range.

Finland joined Nazi Germany in the Continuation War in 1941, seeing a chance to reclaim lost territory. At the time, the Ilmavoimat had approximately 235 aircraft, with just about 200 deemed operational.

From the first day, June 25, when the Soviets attacked numerous Finnish airfields and towns, the Ilmavoimat was stretched thin with approximately 116 fighters (34 Brewsters, 26 Fiats, 27 Moranes, and 30 Fokkers) versus over 500 Soviet aircraft on the Finnish front.

LeLv 24 engaged several times that day, claiming a total of ten kills with no losses. Only five minutes from base, two pilots engaged 27 Tupolev SB bombers below 5,000 feet in the initial battle. Staff Sgt.

Eero Kinnunen and Cpl. Heimo Lampi exchanged passes many times, both claiming five kills. Lampi stated in his after-action report, “I gave pursuit, and the adversary suddenly closed in on me, causing me to draw up beside him.” “At this moment, the rear gunner fired a close-range shot at me.

I drew up behind the bomber and banked again, firing a quick burst into it, causing a fire on its right side. It then landed on the lake, which was on fire. I also witnessed Staff Sgt. Kinnunen shoot down two planes.” By the conclusion of the month, the scoreboard showed seven additional wins and one loss due to an accident.

Three Finnish pilots—Warrant Officer Juutilainen and Sgt. Maj. Lauri Nissinen of LeLv 24 and Sgt. Maj. Oiva Tuominen, a Fiat ace of LeLv 26—tied for first place with 13 wins apiece in the first seven months of the war.

By the end of the year, LeLv 24 had shot down 135 Soviet aircraft, with just two casualties (one due to battle).

Three of LeLv 24’s Brewster aces gained arguably the most renowned Finnish mascot of the period in between combat missions. At the start of the Continuation War in July 1941, 1st Lts. Jorma Karhunen (26.5 Brewster wins) and Pekka Kokko (10) paid a visit to Sgt. Maj. Nissinen (22.5), who was recuperating from wounds in a hospital.

Peggy Brown, a nice Irish setter, presented herself to the flyers, who talked with the dog’s owner. Because feeding pets was difficult due to rationing, the pilots decided to keep Peggy Brown for the duration.

She sweated through combat missions while listening to her comrades’ voices in the base radio room, according to squadron folklore. The flyers kept their promise and returned Peggy Brown to her owner before the end of 1944.

To avoid becoming obvious targets for Soviet bombers, Finnish squadrons moved once a month or more and dispersed by flights. There were occasions when they couldn’t get enough aircraft fuel from Germany.

The Brewster was chosen by the Finns in part because it could run on 87-octane aviation gasoline, which was the European standard until Britain obtained 100-octane fuel in 1940.

LeLv 24’s stockpile was gradually depleted as a result of ongoing battle and attrition. Only 24 Brewsters remained operational by early 1943, forcing additional squadrons to switch to Me 109s during the following year.

Given their ability to kill or damage important targets, Finnish fighters prioritized twin-engined Tupolev SB-2 and Ilyushin DB-3 bombers. Brewster pilots, on the other hand, often encountered Soviet aircraft. 1st Lt.

Wind (39 wins in a Brewster), Warrant Officer Juutilainen (34), and 1st Lt. Jorma Karhunen (26.5) were the top three Sky Pearl pilots, with 23 Polikarpov I-16 monoplane fighters, 18 Polikarpov I-153 biplane fighters, and 11 Hawker Hurricanes.

Until the Finns started converting to Messerschmitts in early 1943, encounters with more contemporary Russian fighters—Yaks, MiGs, and LaGGs—were uncommon.

Juutilainen was a 27-year-old Winter War veteran with three kills flying the Fokker D.XXI when the Continuation War began in June 1941. He was frequently in battle while flying against the Soviets with LeLv 24, earning quadruple kills three times in a day on his way to the top of Finland’s ace list.

When Juutilainen switched to Brewsters, he described the 239s as “fat hustlers, exactly like bees.” They were quick, agile, and possessed excellent weapons…. We were more than delighted to take them wherever and pit them against any opponent.”

In his book Double Fighter Knight, Juutilainen mentioned his two Mannerheim Crosses as examples of his battle experiences. To guarantee deadly precision, he limited his strikes to the shortest possible range.

Juutilainen described a close-quarters combat with a Soviet Hurricane as follows:

I came in at a high rate from above and behind, then slowed down to idle. In my gunsight, the target got larger. It was a spotless aircraft that seemed to be spanking new. As I got closer to the ideal shooting range, I took another look around.

There were no more opponents in sight. My glide angle was approximately 10 degrees, and the pipper on my sight was just barely in front of the Hurricane’s nose. On the target, I could now count rivets.

Wind started the Continuation War as a 21-year-old lieutenant, unlike such seasoned veterans as Juutilainen and 32-year-old Maj. Eino Luukkanen (56 wins). Early in his career, he discovered his shooting eye and earned ace status in six scoring contests.

The Finns were always fighting to maintain their Brewsters functioning due to a lack of external supplies.

As a result, the Ilmavoimat’s inventive, hardworking technicians and engineers worked tirelessly to supply replacement parts, while crew chiefs traveled in their assigned plane’s luggage compartment during their numerous movements to staging locations.

LeLv 24 Brewsters claimed 477 victories between 1941 and 1944, losing 19 in battle and six more in accidents or on the ground.

Many have claimed that the Finnish Brewsters had the greatest victory-loss ratio of the war, but in reality, the Grumman/Eastern FM-2 variant of the F4F had that honor. The “Wilder Wildcat,” which flew from escort carriers in 1944–45, had a 32-to-1 ratio, easily the highest of the piston period.

The Finnish air force upgraded four of its six fighter units to Messerschmitt Me 109Gs in early 1943 and early 1944, but the other Brewsters remained active until the conclusion of the war.

The German fighter aircraft was inadequate to skilled Brewster pilots. Corporal Lampi subsequently told historian Dan Ford about his connection to the Brewster. “My next aircraft after the Brewster was an old buddy Messerschmitt, which was a very hard fighter, although it lacked in humaneness,” Lampi recalled.

“I couldn’t love it as much as I loved Brewster, my best buddy. “Nor, for that matter, any other plane.” Lampi aced the Brewster and went on to win eight more games in the 109.

The Pearls were flown by LeLv 24 until May 1944, when the survivors were transferred to LeLv 26, which had 35 wins with the type. On June 17, 1944, the squadron earned the Brewster’s last win against the Soviets, nearly three years to the day after the type’s first battle.

However, Helsinki’s weakened geostrategic position prompted a deal with Moscow in September, in which Finland agreed to withdraw German troops from its borders. By that time, the Brewsters had grown old and were nearly unsupportable.

During the seven-month Lapland War, the Finnish Brewster pilots conducted their last missions against the Luftwaffe. On October 3, ground controllers vectored LeLv 26 aircraft into the Gulf of Bothnia to intercept a dozen Junkers Ju 87Ds attacking Finnish commerce.

The Brewster’s involvement in World War II came to an end when First Lt. Erik Teromaa and Staff Sgt. Olva Hietala both claimed Stukas. Only eight Sky Pearls survived at the conclusion of the battle. Five remained in the air until 1948, before being retired in 1953.

For decades, aviation enthusiasts have mistakenly believed that Finland’s squared-off swastika symbol was equivalent to Nazi Germany’s slanted black mark.

The Finnish blue swastika on a white background has been the nation’s military emblem since 1918, while the German version of the traditional good luck symbol was not officially accepted until 1935. The Finns adopted a blue-and-white roundel towards the conclusion of the conflict.

With 39 wins in type, Wind was the most successful Brewster pilot. In the aircraft coded BW-364, Juutilainen scored 28 of his 34 Brewster victories. Other pilots contributed another 14.5 kills to BW-364, making it the most successful US-built aircraft of all time with 42.5 credited kills.

Thirty-six of Finland’s 96 best fighter pilots, including six of the top ten, became Brewster aces. In Brewsters, four Finns scored 20 or more wins, a record only five P-47 pilots in US service have surpassed.

Juutilainen ended with 94 wins in all aircraft types, Wind with 75, and Luukkanen with 56. Only one of the three Finns with career totals above 40 flew Brewsters.

There is just one Buffalo variation left today. In 1942, a Soviet Hurricane damaged Finland’s BW-372, which was abandoned in a lake near the Russian border. It was discovered in 1998 and bought by a Florida museum in 2004 before being returned to Finland in unrestored form to be displayed at the Finnish Air Force Museum. MH

Barrett Tillman contributes to Historynet on a regular basis. He suggests Kari Stenman’s Finnish Aces of World War II and Richard S. Dann and Steve Ginter’s Brewster F2A Buffalo and Export Variants for additional reading.

Military History magazine published this piece. Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Facebook for additional updates:

The annals of the brewster buffalo is a book that tells the story of how Finland’s Brewster Buffalo was an unlikely fighter plane.