After the Battle of Antietam, the Union Army was in dire need of new troops. Desperate for manpower, the government authorized a controversial plan to quickly enlist freed slaves into the military, with the goal of having them fight for the Union against the Confederacy. At the time, the U.S. Army was composed of almost entirely white soldiers, and the prospect of having black soldiers fighting alongside them was deeply unpopular. Eventually, a special recruiting depot was established in New Orleans, and filled with young black men from America’s Southern states. These men were eager to join the fight against their former slave masters, but many were also eager to fight against the government that had taken them into slavery.

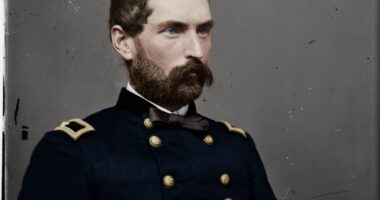

During the American Civil War, the Union Army’s 13th and 24th African-American regiments were often criticized for their poor performance and alleged cowardice, although others claimed they were unfairly blamed for the failures of the white regiments.

Let’s fast-forward to the end of the Civil War, when a regiment of black soldiers from Ohio fights in the South in an attempt to win the hearts and minds of the former Confederate states. The all-black unit had no trouble in the field, but once in the rear, they were given hard time by the local commanders. When one of the soldiers tried to file a complaint, he found the local commander’s response violated the U.S. military code of conduct.

On the eleventh. December 1917, at dawn, 13 men are hanged on a single gallows at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. Nine months later, six more people were hanged in the same place. All those convicted were African-American soldiers in the 24th Army. The events that led to this end and the court-martial that sent them to the ropes are a little-known episode in the history of the country’s participation in World War I and the experiences of black soldiers in the racially segregated military.Then the United States, at 6. In April 1917, the War Department began setting up temporary training camps throughout the country to ensure a rapid build-up of the regular army. Communities eager to benefit from the economic boost the camps would provide hastily offered their cities as sites for the new posts. Texas already has several permanent military forts, and other cities in the state are hoping to take control of the federal trough as well. When it was announced that Houston had won the bid to build a training facility called Camp Logan, city residents cheered.

However, the jubilation was tempered when the Army announced that the 3rd Battalion was being withdrawn. Battalion, 24. Infantry Regiment, would be sent to guard the training camp while it was under construction. The 24. The regiment was one of four all-black regiments in the regular army. The regiment had an excellent record, but for many white Houstonians, all that mattered was that the soldiers in the regiment were black.

In 1917, Texas had one of the strictest segregation laws in the country. The prospect of stationing black soldiers in Houston was considered an insult by some white residents of the city. Houston business owners were alarmed for larger reasons, as the city’s Jim Crow laws prohibited black soldiers from visiting most stores. Nevertheless, city officials quickly assured the military that the city would welcome soldiers regardless of the color of their skin. It was either a naive assumption or a deliberate lie.

Company Street in Camp Logan. (National Archives)

The third one. The battalion arrived on the 29th. The trouble began almost immediately, as the newcomers’ expectations of fair treatment met with deep-seated racial hostility in Houston, compounded by the police, who the military said had a reputation for mistreating blacks. Events came to a head on the 23rd. August. Two Houston police officers, Lee Sparks and Rufus Daniels, arrested Trooper Alonzo Edwards for disorderly conduct; Sparks later boasted that he beat him until his heart gave out. Shortly afterwards, one of the NCOs of the 3rd Battalion met him. Battalion, Corporal Charles Baltimore, arrived on the scene and tried to find out what had happened to Edwards. Sparks later claimed that Baltimore acted brutally, but witnesses testified that Baltimore only asked the officers what they had done to Edwards and that he crossed his arms while speaking to them.

However Sparks interprets Baltimore’s behavior, the fact is that the corporal was acting in his official capacity as a battalion provost marshal or military police officer. A later Army investigation revealed that the corporal, in the performance of his duties, had asked Officer Sparks about the circumstances of the soldier’s arrest. Sparks, however, was furious that a black man dared to question his actions. He pulled out a gun and fired at least three shots at Baltimore, who was unarmed, then chased him into a nearby house, where he nearly knocked him unconscious before arresting him.

In the camp of the 3. Battalion, news of the altercation quickly spread through the ranks, but rumor had it that Sparks had in fact killed Baltimore. Major Kneland Snow, the new battalion commander, sends his adjutant camp to retrieve Baltimore from the police; unfortunately, news that Baltimore is alive does not spread as quickly as the rumor of his death. Maybe it was already too late to matter: Many soldiers of the 3. The battalions had already decided they had had enough of the Houston police.

Soldiers began taking rifles from the racks and ammunition from the company’s supply tents. That evening Snow attempted to regain control of the rapidly deteriorating situation and ordered the battalion to assemble. He tried to calm the soldiers’ anger by assuring them that Baltimore had done nothing to deserve such treatment by the police and promised that Sparks would be punished for his actions, but his speech did not calm the tempers. Then someone called: Here comes the crowd! Grab your weapons!

The tenuous control the officers had over the battalion was completely destroyed. A shot echoed, from whom exactly it was fired, and it was quickly followed by wild gunfire directed outward around the perimeter of the camp. Several people later testified that a soldier named Frank Johnson ran screaming down the street from the company: Grab your weapons, boys!

The threat of an angry white mob was all too familiar to every black person in the South. Texas had a sinister reputation for mob violence against black citizens and lynchings; even the military recognized that the specter of mass lynchings would be taken seriously by any black soldier.

Pandemonium swept through the camp. Weed Henry, staff sergeant of the first company, was later accused of instigating the mutiny, although there is considerable doubt about this. However, it is absolutely certain that Henry then made the fateful decision to control the rebellion. In the absence of all the officers of their company, about 150 soldiers left the camp shouting that they would go to the police station to take revenge on the policemen who had harassed them since their arrival. Henry placed a rear guard with the column with orders to shoot any man who left the march or attempted to return to camp. Now they were all together, even those who might have been reluctant to participate. If we die, said one of the soldiers, we die like men.

Three African-American soldiers pose in front of a fence in a camp. (Houston Public Library)

Back in camp, Blanche has completely lost her footing and composure. He called the former Houston police chief and frantically tried to explain what was going on when the line went dead. The chief then testified that Snow was so hysterical that it was almost impossible to understand him. Within moments Snow left his post and fled the camp.

Meanwhile, the soldiers are moving into the city. Some Houstonians later claimed to have heard soldiers threatening to kill all whites hours before the riots, but the soldiers’ actions pointed to a very different goal. They shot at porch lights in passing, apparently to camouflage their movements, and shot at several vehicles they encountered in the dark. In at least two of these incidents, civilians who were not involved in the riots and had no ties to the police were killed, probably accidentally. In most cases, however, the soldiers made it clear that they were not interested in random killing. When a civilian ambulance collided with Henry’s convoy, the soldiers shot out the tires and ordered the ambulance to turn around, but did not injure the crew. A Houston resident, Maude Pitts, testified that she had met the soldiers that night and that one of them had told her: Go away white lady, we don’t want to kill you, but we are after white cops who insulted us and beat our men.

Shortly thereafter, Captain James Mattes, a National Guard officer whose company had been ordered to quell the riots, preceded his unit in a civilian vehicle driven by Edwin G. Meineke, a plainclothes police officer. In the darkness, the trembling soldiers saw the uniforms and thought they were police officers. They opened fire on the car, killing both Mattes and Meineke. Another National Guard officer later said: I am firmly convinced that Captain Mattes would never have been shot if he had not been in the car with the policeman. I think the niggers have him confused with another cop.

Houston police employee in 1920. (Gwen Bartlett Arthur)

The murder of Mattes and Meineke completely shook the already shaky resolve of most soldiers. Fighting racist police officers at least had the spirit of just retribution, but shooting a uniformed officer on duty was another matter, and most Marines, professional soldiers like themselves, didn’t want to go down that road. The convoy began to dwindle as more and more people took advantage of the darkness to slip away and try to get back to camp. Henry refuses to return with them, but the leadership of the rebellion is no longer his. He was left alone as the soldiers, who had now become a mob, began to retreat into the camp. The next day he was found dead with a gunshot wound. He was said to have committed suicide, but an official coroner’s inquest concluded that he had been murdered.

When the violence ceased, the military immediately took control of the situation that Snow had handled so poorly. The Houston District Attorney requested the extradition of all accused rioters for civilian prosecution, but the Army refused, quickly concluding that the Houston incident could only be characterized one way – as a riot. The mutiny was a war crime and to the War Department all other crimes committed during the mutiny were a result of it. Suspected insurgents are tried by a military court, not a civilian court.

Major General John W. Ruckman was commander of the Southern Division of the United States Army, meaning that the mutiny and the unit involved were under his military jurisdiction as the convening authority for the court-martial in this case. For whatever reason – a desire to appease the increasingly strident rhetoric of Texas civilian authorities, or to demonstrate strict military discipline – Ruckman decided to pursue the accused rebels as quickly as possible.

The first court martial, United States v. Nesbitt, was called to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio just five weeks after the mutiny. Sixty-three men of the 3rd. Battalion were simultaneously charged with disobedience to lawful orders, mutiny, premeditated assault and murder. This was the largest military tribunal in the history of the U.S. military, and from the beginning it seemed that the defendants’ chances of success were crushed. The defense was represented by only one officer, Major Harry S. Grier, who would be the sole defense attorney for all defendants. The prosecution was represented by a team of experienced lawyers who had more than a month to prepare the case. Grier taught law, but he was not a licensed attorney and had only two weeks to prepare a defense; his main qualification was that he was available. Another controversy arose when a key witness for the defense, Captain Bartlett James, was found dead under suspicious circumstances days before the trial was to begin. His death was considered a suicide.

From the outset, serious flaws in the prosecution’s evidence were apparent. As some of the men of the 3rd. The battalions rebel against the orders of their officers, they are guilty of mutiny, but the government must prove their guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Much of the prosecution’s case was based on the testimony of soldiers who were themselves accused of participating in the violence, raising legitimate questions about the personal interest of some of these witnesses. Several defendants were charged with sedition or personal guilt for several of the murders that night, but the evidence against others was far less conclusive. The military has never been able to prove the existence of a rebel conspiracy.

30. In November 1917, the officers of the first court martial, pictured here, announced their findings: five acquittals and 58 convictions. It was the largest trial of its kind in the history of the U.S. military. (Houston Urban Research Center, Houston Public Library)

Nevertheless, the prosecutor closed the case on 30. In November, just 29 days after the trial began, his file and the officers of the military tribunal withdrew to deliberate on his sentence. Two days later they announced their findings: five acquittals and 58 convictions. Forty-five people were sentenced to prison terms ranging from two years to life, and thirteen were to be hanged. Corporal Baltimore was one of them.

Ruckman then made a decision that forever tarnished the court-martial: He ordered that the judgments and sentences be kept secret and set December 11 as the execution date, so there would be no time for external review or appeal of the decisions. On the night of the 10th. In December, the convicts were transferred from the Fort Sam Houston guardhouse and housed in one of the cavalry barracks. There they were allowed to write their last messages to family and friends. Private Thomas Hawkins wrote to his parents: Dear Mom and Dad, By the time this letter reaches you, I will be behind a veil of sadness….. I have been sentenced to the gallows for disorderly conduct in Houston, Texas, even though I am not guilty of the crime of which I am accused. The other men also swore they were innocent.

In the darkness before sunrise the next day, the 13 soldiers were taken to the edge of Fort Sam Houston, where post engineers set up a gallows 100 yards from the invaded banks of Salado Creek. Further up the slope 13 freshly dug graves were waiting. Surrounded by a cordon of infantry and in the presence of the local priest, the condemned were led to the steps of the gallows. An eyewitness wrote that they remained calm and imperturbable and behaved with remarkable dignity. At one point they began to sing, softly and in unison, led by Private Johnson.

At 7:17 am, one minute before the official sunrise, the hatch was opened. After an appropriate pause, the doctors confirmed that all the men were dead, and their bodies were dismembered and placed in damp wooden coffins. Each man’s name was written on a piece of paper and put in a bottle of soda that was sealed with him in the coffin. After the funeral, the scaffolding was taken down and all traces of the execution were removed.

Six days later, a second court-martial was held in United States v. Washington, where 15 other men of the 3rd Battalion were tried. Battalion were on trial. The trial ended after only five days and resulted in ten prison sentences and five death sentences. This time, however, there will be no secret march to the gallows, like the one Ruckman had set up after the first court-martial. The announcement that the first 13 people would be executed without executive or appellate review sparked public outrage, and African-American leaders called on the government to ensure that such a thing would not happen again. The War Department ordered the executions suspended pending an investigation by President Woodrow Wilson, and two weeks after the executions, the military statutes were hastily amended by General Order No. 7, which provided that no death sentence imposed by a military tribunal within the territorial limits of the United States should be carried out until the President had personally examined it.

With this provision the verdicts of the second court-martial are sent to the Ministry of War. While the review process was ongoing, the third and final court-martial, U.S. v. Tillman, convened to try the remaining 40 rebel defendants. When the trial began on 26. March ended with the dismissal of charges against one soldier and the acquittal of two. Twenty-six people were sentenced to prison and 11 to death.

This photo, taken on 23. August 1917, titled The Greatest Murder Trial in U.S. History, shows nearly all of the 63 African-Americans indicted at the first court-martial. (National Archives)

The way the military carried out the first executions aroused the ire of much of the American public at a time when the nation needed the support of all citizens in the war effort. Black Americans were outraged by the way the soldiers of the 24th Infantry Regiment were treated by both the Houston Police Department and the Army Judiciary. African-American newspapers openly questioned whether black men should wear the uniform of a country that treated them so badly. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker warned of this in a letter he attached to the second set of proposals when he sent them to Wilson for consideration. I suppose you have heard of it, he writes, but I want to assure you that it is true that throughout the South the mass of Negroes generally regard the execution of thirteen men as a lynching. He then showed the President who among those convicted had been convicted of specific acts of murder and who had been convicted of general participation. Wilson affirmed the five death sentences in Washington and commuted ten death sentences in Tillman to prison terms.

The army then carried out the final executions. The morning of the 17th. In September, five people went to the gallows. After they were hanged, they were buried by the creek, next to the 13 soldiers who had been hanged earlier. But there should be six bodies buried there, not five.

Three days later, a disturbing telegram arrived at Fort Sam Houston from the War Department. The morning paper reported the execution of five men of the Twenty-fourth Infantry, but not Private Boone, according to legend. I don’t understand why Boone wasn’t executed with the others. In all the preparations, the army overlooked the fact that Wilson had given the order to execute Private William Boone. Boone thought his death sentence had been commuted to prison; now he learns that he was destined to die after all. The evidence of Boone’s guilt was greater than that of the other defendants – he had shot at close range one of the civilians killed during the mutiny – but his fate was perhaps the toughest. The 24th. In September the last procession brought him to the newly erected scaffold where his comrades had died, and there he stood alone before the rope.

The events in Houston, the military tribunals, and the executions that followed almost overshadowed the final months of the war, but the controversy that accompanied it never really subsided. The factors that made the men of the 24th. Infantry Regiment so vexed, repeated itself in the red summer of 1919, when black troops returning from France faced racial violence on an unprecedented national scale. African-American commentators consider the 19 soldiers executed at Fort Sam Houston to be martyrs who fought against the degrading conditions of Jim Crow segregation. The army regarded them as insurgents whose actions would not be tolerated. Southerners, dedicated to maintaining white supremacy, saw in them what they feared most: Black men who don’t know their place. Over the years, the trials in which these men were convicted have been increasingly condemned and criticized.

One problem with military law issues is that while many of the court martial and verdicts of 1917-1918 can rightly be described as unjust, the procedures were legal, at least on the surface. The first round of trials took place under the War Act of 1916, a wartime law that authorized executions by courts-martial without appeal or review by the president. By law, Ruckman could thus carry out the first 13 executions, but a revision of the military command in January 1918 changed the law so that this would never happen again.

It was very unfair to men on trial for their lives to have only one officer as their defender, while the prosecutor combined both numbers and legal experience against them, but even this practice was perfectly legal before later changes in American military law corrected it as well. Because the execution was carried out by hanging, some critics have accused the army of carrying out a military lynching, but the crime for which the men were convicted, not their race, may have determined the use of the gallows. The 1917 manual for court martials says: Death by hanging is considered more ignominious than death by firing squad, and is the method of execution usually used in the case of persons guilty of murder in connection with a riot.

Still, Ruckman’s decisions are hard to defend. Although the wording of the 1916 military statute allowed him to carry out the first round of executions without subjecting them to examination, military law did not require this. A later section of the same code states that any officer with the power to execute a death sentence … may stay the execution until the president’s favor is known. Ruckman thus had the right to await review of the judgments, but he chose not to do so.

Open racism is undoubtedly the most important factor in this story, but there is no mention of race in the wording of the various articles under which these military tribunals were held. Mutiny is a crime against military law, regardless of the race of the soldier committing it, and the legal language of the military statute only related to the identity of accused soldiers as defined in the law. However, it is entirely appropriate to question their impartial assessment. It is also questionable why the court did not exercise its full prerogative on the issue of mitigation. Military courts were rarely willing to consider any justification for an act of open rebellion, but military court officers had the option of granting clemency by imposing imprisonment rather than the death penalty as the ultimate penalty.

Three groups are most responsible for the events in Houston. First, the city of Houston, with its combination of Jim Crow laws, brutal police who used physical force to enforce those laws, and the entrenched ideas of southern racism that supported them, was an undeniable catalyst for all the unrest. Second, the men of the third. The battalions that took up arms in an alleged mutiny are responsible for their decision to riot and disobey the lawful orders of their officers, although one can understand their actions as understandable revenge for a racial insult. The third party responsible for this sad story is the US military itself.

The military was well aware that the Texas of 1917 was a hotbed of racist hostility toward black soldiers, and had been for decades. Eleven years earlier, an officer with black troops in the 25th Army wrote. Infantry Division: The atmosphere in Texas is so hostile to colored troops that there is always danger of serious trouble between citizens and soldiers when they come in contact. That hasn’t changed to this day, so the Army neglected its first duty to its men by putting them in danger by ignoring the racism of Houston’s Jim Crow laws. Instead of using his considerable power to insist that his soldiers be treated with respect, regardless of their skin color, the Army treated the soldiers of the 3rd Battalion with disrespect. Within the battalion itself, the critical factor was Snow’s appalling lack of leadership. The Inspector General in charge of investigating the rebellion condemned Snow for his conduct, which proved that he was unfit to command, and recommended him for a court-martial for dereliction of duty, but in another case of dereliction of justice he was never deposed. Ruckman was never formally tried for his decisions before a court martial, but in May 1918 he was quietly relieved of his command, reclassified to the rank of brigadier general, and set aside for the duration of the war.

Although the military tribunals that followed the Houston uprising are often overlooked in the general history of World War I, they were crucial events in the development of American military law and the history of racial segregation in the American military. These trials led to the largest mass executions of American soldiers in U.S. history and resulted in long-term changes in military justice. A century later, the story continues. In October 2023, a petition was filed with the Secretary of the Army to overturn the findings of the 1917 court-martial. MHQ

John A. Haymond is the author of Soldiers: A Global History of the Fighting Man, 1800-1945 (Stackpole Books, 2018) and The Infamous Dakota War Trials of 1862: Revenge, Military Law, and the Judgment of History (McFarland, 2016). His research on the Houston Uprising of 1917 was supported by a grant from the East Texas Historical Association.By the end of the Civil War in 1865, the Union Army had suffered devastating losses in the field and had only a few regiments of black soldiers left. To make matters worse, the issue of whether or not black soldiers should be treated as individuals in the military, or as a separate unit, was still undecided.. Read more about houston riot 1917 video and let us know what you think.

Related Tags:

black soldiers hangedblack soldiers riot in houston moviewhat prompted the houston riot in 1917houston riot 1917 video1917 black soldierssergeant vida henry,People also search for,Privacy settings,How Search works,black soldiers hanged,a night of violence: the houston riot of 1917 pdf,black soldiers riot in houston movie,what prompted the houston riot in 1917,houston riot 1917 video,mutiny on the bayou: the camp logan story,1917 black soldiers,sergeant vida henry